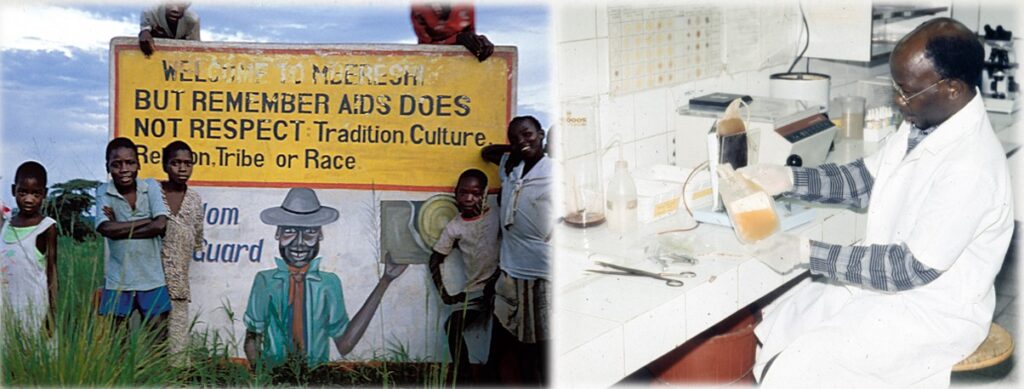

AIDS: Why Africa?

Patient-Safety in Africa 2023

Sex or needles? (2018)

In early August 2022, thirteen studies were reported describing HIV (AIDS) sequences in specific populations in Africa (Gisselquist 2022). By finding similarities in viral lineages, it was possible to estimate what forms of transmission had occurred.

In principle, the HIV-(AIDS)-Virus can be spread through sexual contact or through contaminated blood products (or needles). The authors of the comparative analysis concluded that a significant proportion of HIV infections in Africa actually occurred in health care settings.

These risks and associations have been highlighted in Africa for over thirty years. And it was consequently since 1990 is recommended many times in publications:

- therapeutic injuries to the skin (by needles, instruments, scalpels …) should only be allowed under strictly sterile conditions,

- and only if they are really absolutely necessary, taking into account the benefits and risks.

To date, cases of illness and death could have been prevented in this way. Reasons why this often did not happen are

- Lack of liability regulations (e.g. for international organizations that carry out interventions involving skin injuries as part of campaigns)

- Ignorance, suppression or lack of concern on the part of medical professionals („a lot helps a lot“)

- Commercialism („share holder value“),

- ideology („eradicate the problem“)

- Power („paternalism“)

First of all, a legally enforceable liability would be necessary in the context of medical development cooperation. That is, those who do harm (e.g., through risky programs or therapies involving needles or other instruments) would have to be held accountable in the event of harm. However, „accountability“ is a foreign word for very many who intervene in Africa for ideological or commercial reasons.

Questions & answers

In 2011, Grimm and Class [1] urged Germany’s Development Bank (KfW) to pay attention to evidence “an important share of new infections in high prevalence settings occurs through blood exposures in formal and informal healthcare,” and called for “interventions targeted to strengthening the health care system in general and infection control in particular.”

Questions (send to KfW, 22.10.2017)

- What conclusions did KFW 2012 draw from the analysis of the authors Grimm and Class of 2011?

- To your knowledge, have there been epidemiological studies on HIV outbreaks ever since that time…?

- What measures does KfW support to prevent iatrogenic and nosocomial infections (especially hepatitis C and HIV)?

Answer (from KfW, 19.01.2018)

(Patrick Rudolph, KfW, Sector Policy Unit Health & Social Protection)

… thank you for your interest in the position and commitment of KfW Entwicklungsbank in the field of infection prevention.

… The key factors for the direction and design of such [HIV] projects are therefore the partner’s sector strategy considerations and the corresponding guidelines of the Federal Government (including the strategy for the control of HIV, hepatitis B and C and other sexually transmitted infections).

We support … a differentiated, demand-oriented and multisectoral approach to HIV prevention depending on the specific micro-epidemiological constellations. This may include measures to prevent both sexual and iatrogenic infections… [I]n South Africa – currently the only country in which the fight against HIV is the focus of German development cooperation in the health sector – the focus is clearly on preventing the sexual transmission of the pathogen …

Response (Jäger, 19.01.2018):

„… thank you very much for your reply … Unfortunately, you have not answered my specific questions.

As early as 1990, we had already published that with regard to infections caused by the health care system, the technical equipment of blood banks was not able to solve the quantitatively much bigger problem (unnecessary indications, lack of user hygiene and improper handling of needles and syringes). The consequence of this knowledge should have been investments in the control and prevention of dangerous medical applications. This is evidently not done for the most part…

Are you really sure that…HIV proliferation in South Africa, for example, can only be explained by sexual activity? My doubts intensify among other things a study of 2014 (Kharsany 2014[3]) describing the dynamics of HIV infection of high school students in rural South Africa: 6.8% of girls were infected [including many self-reported virgins]… Where these girls infected themselves with HIV … remained unclear …“

This dialog might be challenging for those who pay for HIV prevention programs to reconsider their lack of attention to HIV from unsafe healthcare.

References:

- Büchner A: Nosocomial outbreak of hepatitis B virus infection in a pediatric hematology and oncology unit in South Africa. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62:1914–1919Correa M et al: Blood Borne HIV. Longman 2008.

- Gisselquist D et.al.: Recognizing and Stopping Blood-Borne HIV Transmission in Africa, SSRN, 02.08.2022

- Gisselquist D: Stopping Bloodborne HIV, Adonis&Abbey 2020 –

- Grimm M, Class D. The fight against HIV/AIDS must be brought into balance. KFW-Development Research: views on development. No 3, 24 June 2011. Available at: https://www.kfw-entwicklungsbank.de/Download-Center/PDF-Dokumente-Development-Research/2011_06_ME_Class-Grimm-The-fight-against-AIDS-must-be-brought-to-balance_E.pdf (accessed 8 February 2018).

- Jaeger H: AIDS in Afrika. Projet SIDA, Kinshasa 1987-1990 –

- Jaeger H, Gisselquist D, MEZIS Nachrichten 2018, Nr. 3, S. 1-4 –

- Karsany ABM, Buthelezi TJ, Frolich JA, et al: HIV infection in high school students in rural South Africa: role of transmission among students. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2014; 30: 956-965. (accessed 9 February 2018).