Martial arts

Action and meditation are the same. Reinhold Messner

Many (male) martial artists combine their movement training with ‘consciousness work’. They ask about the ontology, the unconditional, or (according to opinion) the either moving or motionless absolute. In the context of everything or of nothing, they trace their ‘I’, the unconscious ‘self’ or ‘mind’ or more far-reaching forms of spirit or connectedness.

Competitive athletes do not waste time on existential questions. Then why do martial artists do it? I suspect because they experience the close relationship between nerve and motion cells. And because they train very effective interactions between attention, intention and the system of fascia, muscles and bones.

Philosophers sitting motionless in front of their laptop and thinking intensively about life and death feel no body at this moment of highest concentration. But the body would have a lot to say on this subject, perhaps even the essentials. Martial artists, on the other hand, sometimes experience the immediacy of the moment in which the dynamics of the locomotor system adapt to the surrounding situation. And in which their attention observes interactions attentively and calmly.

When the mind fidgets, painful feedback occurs: immediately and memorably. Martial artists must therefore not only be interested in techniques that they routinely use, as in other sports. It is at least as important to understand psychological relationships in order to be successful in their bodywork. For example, they learn to focus their attention on the tip of a sword or, conversely, they experience everything at the same time: all joints, fibers, the rhythm of movement and the space-time dimensions in which something happens.

Some martial artists speak of ‘expansion of consciousness’ when they speak of their attention training, because much of what happens unconsciously and automatically in everyday life can first be consciously perceived and questioned in order to change it in a learning way. And because afterwards, when a new movement pattern seems to run smoothly and perfectly on its own, consciousness can look at dynamics calmly without intervening to control them.

If a ‘more conscious’ approach to external stress develops into a careful approach to physical resources, health is promoted. Others want psycho-physical training to increase their immediate, intensity-strong penetrating power in order to achieve very effective victories in the confrontation with physical violence or in the hard everyday life of management. Such goal-oriented training sometimes causes psychological or physical collateral damage to others and to oneself.

If a very high degree of perfection has been achieved in certain movements, martial artists, especially when the potential of physical strength decreases with age, strive to experience immediate, unquestioning knowledge and then call this goal enlightenment or perfect connectedness.

Some of these martial artists develop esoteric secret teachings in which a master (rarely a female), who is close to knowledge, passes on the essence of his wisdom to particularly hard-working disciples. The Master knows the ‘right’ inner path, which leads to ‘deeper’ insights during intensive practice. His students trust and follow him, and they experience parts of themselves in a new or different way.

In such training communities, the control of the frontal brain parts, which create a critically questioning ‘I’ during the rational coping with everyday life, is calmed by rituals, mystical ideas and moving meditations. Temporal cerebrum parts, in which what is heard, practiced and experienced is stored, can then take control. The messages of the internal sensors are thus felt more clearly (evaluated in the midbrain) and finally consciously perceived as they are (without judging them).

The same happens in psychotherapeutic procedures in which physical training does not play a significant role: in suggestion, hypnosis or hypno-systemic coaching. For many stressed people, the triggering of a professional trance can be extremely useful and healing. But of course there is always a considerable risk of abuse, which can lead to addiction, aggravation or mental and physical cramps.

Other martial artists are more closely related to rational, firmly structured and often written belief systems. In this case, attention is less focused on the processual, the internal and external senses, but rather on the ‘correct or wrong’ execution of actions. Truths and dogmas guarantee the firm support of a hierarchical leader, while climbing up step by step under the guidance of a quasi-religious expert. Depending on the climbing height achieved, one then gets a degree, which is demonstrated by stripes on the jacket, impressive certificates or the colors of a belt. While in shamanistic communities of faith the Master is completely filled with the Spirit. And therefore an ‘enlightened one’ has not to be able of anything. He is at the highest point and must not proof it anymore. Nevertheless in dogmatic systems he is regarded as the highest authority, who exhibits the perfect competence of a system of action that is very clearly defined by rules. Of course, he has learned the concept of action developed by him particularly perfectly, and his set of rules excludes what he cannot do. Therefore, as long as he continues training, he always retains a certain competence advantage over his best students. And of course he no longer compares or measures himself with the masters of other schools.

In hierarchical organized systems of martial arts, one’s own practice is often classified in a superordinate, religious, written fixed system of knowledge, such as Zen Buddhism, Dao or Confucianism, classical writings, Christian mysticism, Islamic Sufism, Indian Vedanta, modern quantum theology and many others.

But training martial arts can also open up a third psychological path: without secret teachings or religion. Dealing with the harmonization of bodily functions can stimulate personality development, which can lead to more elastic and flexible handling of internal and external stress. In this case, the trainer take on the role of a consultant or coach. He (or she) doesn’t necessarily know ‘better’, because they themselves are only students with a few years of experience advantage. Others, who learn faster than they do or have better prerequisites, then have a real chance of getting better and eventually surpassing their teachers. The more people experience learning and practicing in such open systems, the more they discover something new and recognize more and more how infinitely many things they neither know nor have experienced. This insight promotes an attitude of friendly modesty, with which teachers and students work together transparently in processes that lead to individual and creative learning processes through shared experience.

Somebody showed me, and I found it on my own. Welch

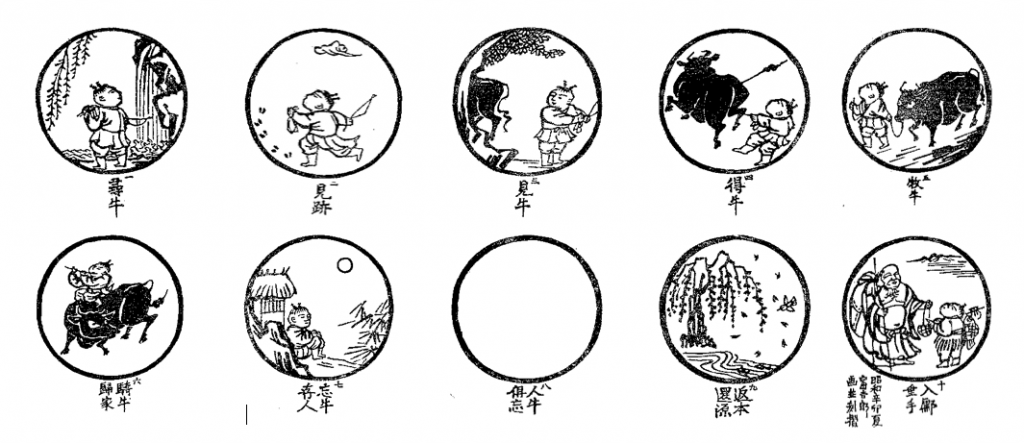

Picture of Tokuriki (16th century). Someone is looking for something: his self (1). He discovers footsteps: he feels and experiences (2). He sees an ox: the unconscious (3). He catches him and fights (with himself) (4). And tames him, calming the inner team (5). He rides, fluting, on him home: he is at peace with himself (6). The ox has suddenly disappeared: Quiet viewing without judging it. (7). Recognition of nothing: the original chaos. (8). Perceiving the flow of life in his relationships without “I, Mind or Self” (9) Being modest, unresisting, unjudging, natural and active in everyday life (10).

What is actually ‘I, Self, Energy, Mind, Consciousness. Spirit, deep level of consciousness, …’?

Words like these are nothing more than arbitrary-divisive terms that someone has come up with in order to use them for something. What such a term ‘is’ has less meaning than recognizing who has named what, why, and what he or she wanted to communicate with it. For example, if someone defines an ‘I’, it is useful to ask what he has excluded as ‘not me’ and for what reason.

Nothing ‘is’. So far, no one has been able to discover anything that is ‘static’. Even the heaps of stones in the pyramids are nothing unchangeable: they change constantly, albeit slowly. Everything in this universe changes and passes. Anyone who yearns for something that remains must therefore actively construct stories about the past, directed towards the future.

But because everything we experience is just emerging, like a source bubbling into an unknown future, even death cannot take anything away from us, for everything that was has already passed away. Only the life energy will consume itself, as with a candle flame, which will extinguish sometime. As long as sparks of energy are still available, however, it can radiate in the many colors of its various components, possibly nourished by meaning and meaning:

Very well, I am big, I am many. Walt Whitman

The ‘I construction’ is artificial

Superorganisms have no limits. Most of our DNA is located in the bacteria in our ‘cells’ (mitochondria) and in bacteria outside the surface. We are an integral part of ecological and social systems. Man therefore resembles a medieval city: with wide open gates, peasants and merchants living outside the walls, many foreign visitors inside and only half closed gates in times of war. Physicists see even fewer limits: They consider many intertwined systems and define something as separate only for tactical reasons in order to view details on it. They tried intensively to find any ‘truth’ in any notions of separation, and have so far failed. So there really doesn’t seem to be anything definable separate (and certainly no ‘I’). But everything changes in relationships and grows constantly new in interactions.

‘Self and I’ are the result of useful, active, energy-consuming processes that can be easily stopped by anesthesia. They are necessary as reference points for incoming and outgoing information. They are useful in distinguishing ‘good or bad for me’ and in assessing actions that should satisfy needs. And they are essential as reference and reference for the calculation of movements (Wolpert 2012). However, the importance of nerve cells (and their thought products) is far overestimated, as they are only parts of feedback loops that oscillate as a whole and are even influenced by bacterial products in the intestines (e.g. during depression). (Douglas 2018)

In all mammals, a primitive ‘I’ flickers in the central parts of the brain.

Awareness arises when information is processed in a special way. It is the result of a highly complex active energy-consuming processing of incoming and outgoing data and their interaction. Almost everything we do is based on the fact that the brain produces expectations and then updates and changes them. For the design of these interactions between input and constantly changing prediction, especially in visual processing, a reference value (awareness) is required.

The spinal cord, brain stem and cerebellum are not required to generate consciousness. The perfect sequence of an automatic movement, such as dancing or playing the piano or climbing, requires no consciousness. The reason may be that the basal centers of movement coordination in the interbrain and cerebellum work rather ‘linearly programmed’ (feed forward): one group of nerve cells influences the next and this in turn influences the next but one. The conscious parts of the brain, especially the cerebral cortex, are stimulated plastically and associatively. (Koch 2018) Rear parts of the brain (including the visual cortex) excite and demand parts of feedback loops, and only as long as this flickering is maintained (in which the body is ultimately involved) consciousness prevails. (van Vugt 2018)

Awareness can be formed, trained and shaped in physical embedding.

Typical of the more complex human ‘I’ construction (in the limbic system and parts of the cortex) is an ‘illusion of free will’, in the sense of ‘I have caused this movement’. However, Rudolfo Llinas, one of the fathers of the neurosciences, had already shown some years ago that even his own ‘self’ wrongly had the feeling of triggering a movement that had clearly been generated from outside. Essential personal memories are also generated again and again actively (as narratives). (Akthar 2018)

Because there is no such thing as an ‘I’, it cannot be broken (e.g. by a trauma). However, the construction processes that lead to ever new constructions of ‘self and I’ can be considerably disturbed by external damage and be considerably defective. This applies in particular to people who have been neglected in their early childhood, who have experienced abuse or violence, or who, as seriously ill patients, feel fear of death.

I think, therefore I am (Descartes). I’m not. So what? (Suzuki).

I’m dreaming, so I am (Crazy Horse). I am not, we are (Tutu).

The De-Construction of ‘I and Self’

„After turning off the boats motor and the running lights, I lied down in silence and darkness … my world had dissolved into that star-littered sky. The boat disappeared. My body disappeared. I felt connected to all nature and to the entire cosmos.“ Alan Lightman, physicist

The ability to construct an ‘I’ is indispensable for individual survival. Children master this basis of social communication (the so-called theory of mind) from about the age of three to five years: ‘I think that you think that I think’. The survival of a social group, on the other hand, is ensured by the de-construction of the ego and the creation of a ‘we-construction’. The first Stone Age immigrants from Africa were no more intelligent than other apes, like the Neanderthals, but, as the biologist Humberto Maturana described it, they distinguished themselves as ‘loving animals’. Typical for humans are strong pair connections (Eros), the support of children, week and sick children and the mutual support in tribes without direct family purchase. The human ability to construct a non-ego (or ego-deconstruction) can be very powerful. For example, it is possible to accept one’s own death to save another’s life. The psychiatrist Victor Frankl, who had survived Nazi concentration camps, therefore considered ‘meaning’ (sacrifice one’s life to s.th) to be the most important principle of human existence. (Frankl 1995)

There is nothing in the world that can so emphatically help people to survive and stay healthy was the knowledge of a meaningful life’s task. Victor Frankl

Opportunities and risks of martial arts

The strengthening of the ‘I’ through martial arts training is obvious: Many start with their training to build up their self-confidence.

Self-defence, however, is less about learning skills than about creating the illusion of surviving violent situations unscathed. Learning and training a martial art reinforces the optimism to cope better with unfamiliar and difficult situations. This increase in self-confidence is essentially based on the improvement of a psychological attitude. The memorization of complicated techniques is less important, because they would hardly be present in an emergency anyway: In an emergency, a friendly studio kick boxer would be hopelessly inferior to a brutally random street gang member fighting in a trance.

Pure mindfulness training (without the art of movement) has shown that stressors can be better recognized and (within limits) avoided. However (without involving some sort of aerobic or mindful movements) the ability of dealing with stress in everyday life will hardly improve (Hafenbrack 2018)

Meditation, yoga and mindfulness exercises do not protect against burnout, however, if they only provide for temporary rest breaks, in order to pedal all the more strongly afterwards in the hamster wheel of foreign and self-exploitation. (Wagner 2018) Dealing with oneself through movement and mindfulness does not lead to humility and modesty, but rather to the feeling of being a little greater than others. (Gebauer 2018)

But, learning a martial art that, in contrast to pure mindfulness exercises, consciously involves the whole body has the potential to develop previously hidden, unconscious, repressed or neglected aspects of personality and to integrate them more strongly into the unity of body and mind. (Wang 2018)

Through physical action, with clearly visible effects, self-confidence grows. And the associated danger of overestimating oneself remains limited if overall contexts and respectful relationships in mutual learning lead to a feeling of solidarity between us. (McGilchrist 2010)

Basic laws and principles of life can be rationally understood and experienced in flow or in trance and are memorized. The effects of feelings on posture, facial expression and prosody of the voice become clearer. And ideally, incorrect postures that developed unconsciously under the influence of stress over the years can also be resolved. The body’s automatics, which are based on brain stem functions, can normalize, calm down. Finally, the brain can step back and let fascia, muscles, intestinal cells and bones do what they seem to master without higher commands, all by themselves.

A Zen monk of the 16th century describes how the wave of consciousness in such states of awake, unbiased contemplation ebbs away and resembles only immobile water. (Takuan 1573-1645) Similarly, Patanjali’s 2,500-year-old yoga teaching aimed at a ‘fluid state in which the movements of the mind are transformed into a dynamic silence’.

In order to achieve such harmonies of physical and mental functions, it is necessary to accept the situation as it is and to look curiously and questioningly at the possibilities that arise. Albert Einstein called it ‘to stand still longer in case of a problem’ and the medieval mystic Eckhart recommended ‘to let oneself stand completely still and as long as possible’. If martial artists take such advice seriously, elements from the Alexander Technique, Feldenkrais, Shiatsu, etc. became much more important to them. First it must be ensured that the basis is doing well (the intestines, the fascia, the bones…), then posture or breathing can be influenced favorably, and finally process-oriented techniques that benefit the body can be learned from inner peace.

The opposite way: training the ‘right’ techniques in a goal-oriented manner and only when these are correctly executed, focusing on the perception of ‘deeper’ body functions, sometimes leads to cramps, which rather hinder the development of well-being.

If you really want to learn something new and grow, you have to assume that you know absolutely nothing. Otherwise, only what is already known is constantly being perfected and solidified until it becomes static. From the healthy attitude of ‘not-knowing and not-capable’ can arise at the same time boundless curiosity and serenity. Then a fertile ground is formed to listen inward and outward, and to develop fertile and meaningful in a psycho-physical unity. And so you can continue to train patiently into old age and experience something new at every moment.

Yoga is the ability to focus the mind exclusively on an object and to maintain this direction without any distraction. Pantanjali 2,500 years ago

References

- Akhtar S et al: Fictional First Memories. Psychological Scienc, 17.7.2018

- Douglas, Angela E. (2018): Fundamentals of microbiome science. How microbes shape animal biology. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Frankl V: Was nicht in meinen Büchern steht. MMV Medizinverlag 1995

- Gebauer JE et al: Mind-Body Practices and the Self: Yoga and Meditation Do Not Quiet the Ego but Instead Boost Self-Enhancement. Psychological Science June 22, 2018

- Hafenbrack AC et al: Mindfulness Meditation Impairs Task Motivation but Not Performance.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 2018,147:1-15

- Llinas R, Roy S.: The ‘prediction imperative’ as the basis for self-awareness, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009 May 12; 364(1521): 1301–1307. Roy S: the neurology of seLf-awareness and buddhist perspective

- Koch C: What Is Consciousness? Nature 09.05.2018, 557:S9-S12 nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05097-x

- McGilchrist I: The Master and his Emissary. 2010

- Takuan Sōhō (1573-1616): Fudóchishinmyóroku: Bewegungslose Weisheit oder die Plage des Verweilens in der Unwissenheit.

- Wang, C: Effect of tai chi versus aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia: comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial. BMJ 2018, 360:k851: https://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.k851 Wagner G: Selbstoptimierung Praxis und Kritik von Neuroenhancement. Frankfurter Beiträge zur Soziologie und Sozialphilosophie 2018, Essay (pdf): Arbeit, Burnout und der buddhistische Geist des Kapitalismus

- Wolpert DM: Principles of sensorimotor learning Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011 (12):739–51 http://cbl.eng.cam.ac.uk/Public/Wolpert, Vortrags-Video: ted.com/talks/daniel_wolpert_the_real_reason_for_brains?language=de

- Van Vugt et al: The threshold for conscious report. Science 2018, 360 (6388):537-542